What is well-being and how can we promote it in dementia?

I displayed this poster at the Royal College of Occupational Therapists’ online conference in 2021.

Well-being, a term widely used in health and social care, is at the top of the Care Act 2014 list of responsibilities of local authorities. But it’s rarely defined, so what does it mean? It sounds as if it belongs somewhere near the top of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and only attainable once our basic physiological, safety and security needs have been met. Moreover, well-being is often paired with health, as if it somehow depends on being physical well.

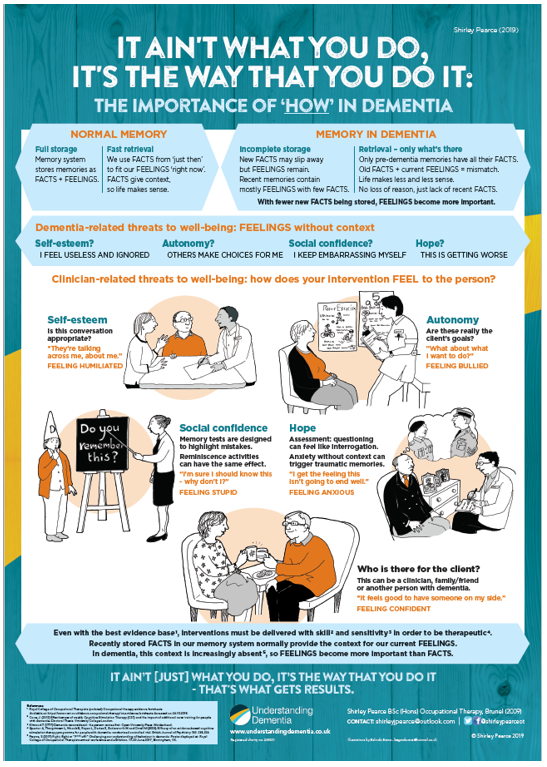

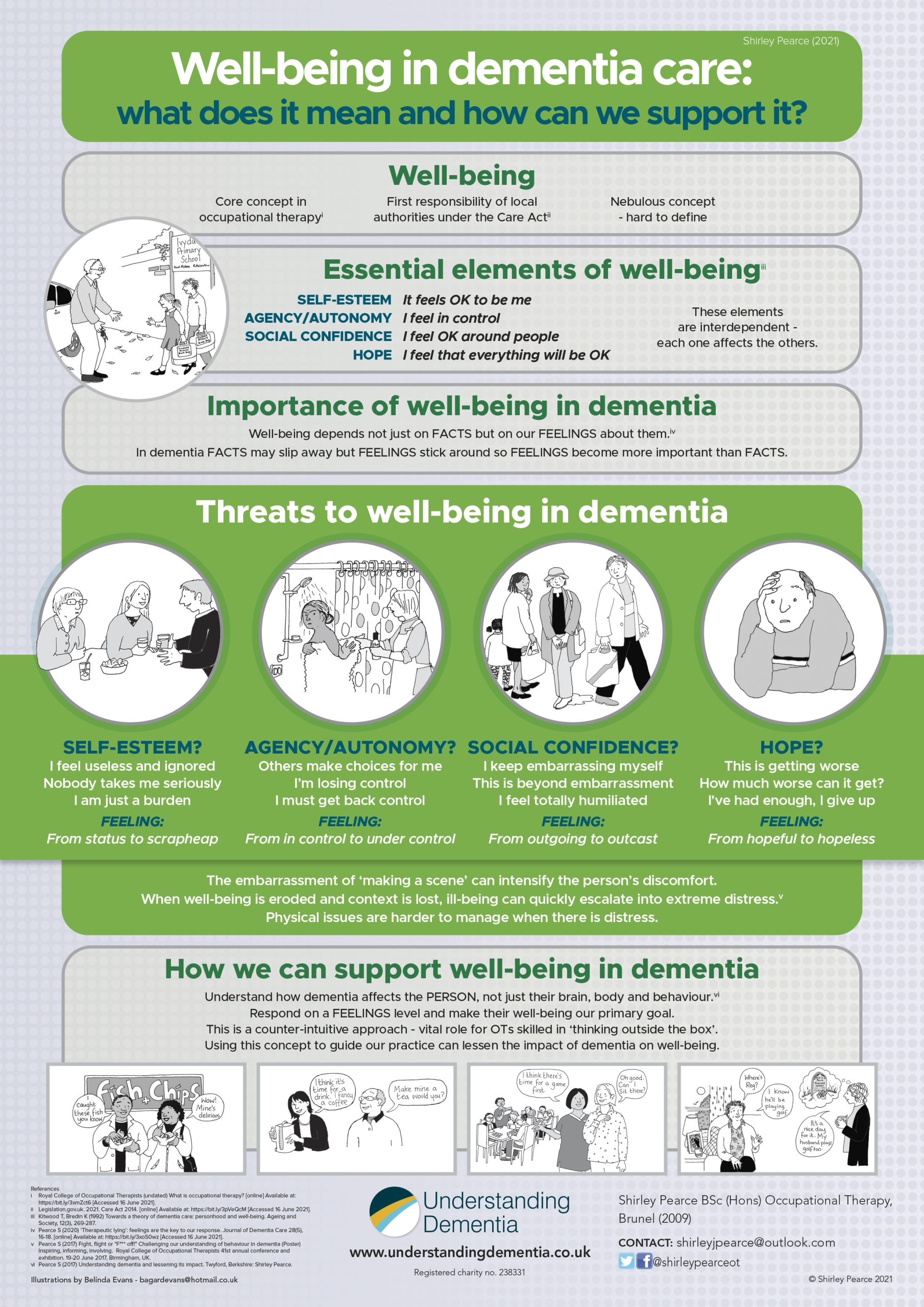

In their 1992 article Towards a theory of dementia care: personhood and well-being, psychologists Tom Kitwood and Kathleen Bredin described well-being in terms of personhood, as a subjective state of mind. They said it depends on four essential feelings: self-esteem, agency (the ability to make decisions and have them carried out, which is closely related to autonomy), social confidence and hope. These four feelings are the pillars that support well-being. These feelings are interdependent: damage to one increases the risk to the others, while boosting one aspect has a positive effect on the rest. This concept of well-being applies to all of us, but it is especially significant in dementia.

Dementia can easily strip away a person’s self-esteem, their sense of agency and autonomy, their social confidence and any sense of hope. Well-being in dementia is therefore precious and vulnerable, but once we understand why that is, we can learn ways to promote it, protect it and even rebuild it.

A sense of well-being does not depend only on the facts of what is happening, but also on how we feel about it. In most types of dementia, the person’s memory system stores facts increasingly unreliably, so feelings assume greater importance. The facts of recent experiences are stored more and more intermittently, while the feelings they generated are still stored as effectively as ever. So the person can experience feelings that make no sense to them, because the facts to explain them have slipped away.

Feeling good, or even just feeling OK, but not knowing quite why you feel like that is one thing, but feeling ‘not OK’ to any degree, without knowing why you feel like that, is quite another. With no context to explain it, even a slightly disconcerted feeling can become distinctly unnerving.

This can easily escalate into extreme distress, resulting in behaviour that’s difficult to manage and disturbing to witness. The discomfort of the person at the centre of it is made worse once they realise they’re ‘making a scene’. We need to understand that they are not so much being difficult as having a difficult time. Distress with no context or explanation is the stuff of nightmares. This makes the well-being of people living with dementia especially vulnerable.

Once someone with dementia is in distress, it won’t help to bombard them with facts or to try and explain their feelings away, as that will feel to them as if we’re not listening. Stress affects cognition, so the person will be less able to retain detailed factual explanations anyway.

It is far better to get alongside them in their distress and to validate their feelings. Once their distress has subsided, they will be better able to cope with our attempts at distraction. Then, when they are engaged in something they enjoy, they may not even recall the facts that led up to their distress, so their well-being can be restored remarkably quickly.

Training from Understanding Dementia includes the art of communicating with the person on a ‘feelings’ level, which makes this a whole lot easier.

Book a place on our interactive online training course for health and care professionals or family carers.