It ain’t what you do, it’s the way that you do it

I often hear colleagues discussing the relative merits of various activities and therapies for people with dementia. Is art therapy better than music? Collage better than watercolour? If anyone asks my advice, I usually say ‘You can use all sorts of things. After all, it’s not what you do…’ Sometimes we don’t need to do much at all.

The wife of a regular at our day centre once asked me: ‘What do they do there? He always says he’s enjoyed it, but he can never tell me what they’ve done.’ He was an older man, and any strenuous activity would have required detailed risk assessments and precautions. So one afternoon when he casually mentioned that he’d been horse riding, she was so shocked that she dropped a full cup of tea down herself! She asked me anxiously, ‘They don’t really ride horses, do they?’ I reassured her that they didn’t, and we never discovered what had triggered the feeling that he’d had a lovely ride. But it hadn’t needed any complicated planning or risk assessments!

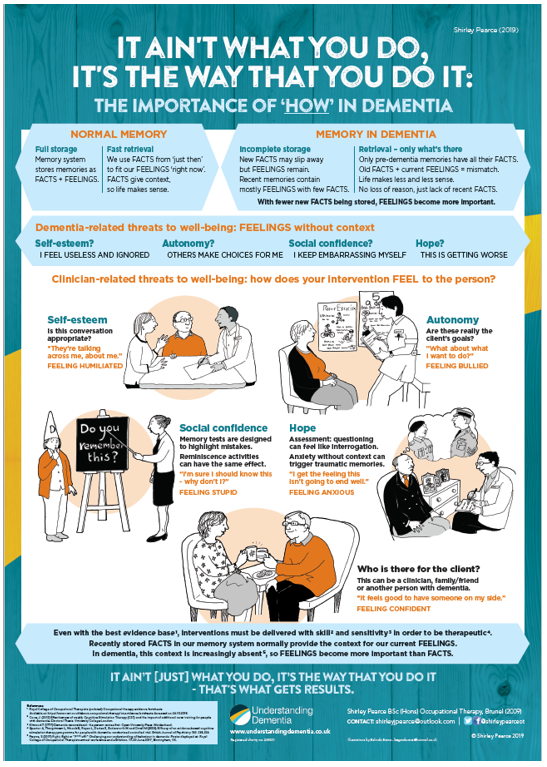

By definition, evidence-based interventions work, assuming that the results of research studies are always objective and generalisable. However, the way we deliver them can have a significant effect on the outcome. When Tom Kitwood coined the term ‘malignant social psychology’ in his book Dementia Reconsidered1 he didn’t have any particular interventions in mind. He was was referring to the prevailing culture and attitudes of healthcare professionals at that time to the people in their care. Thanks to his work and that of others since, things have improved greatly, but there is still a long way to go.

A new intervention is developed by experts, tested under controlled conditions and shown to work. Skilled therapists confirm its effectiveness, and before long, it is identified as best practice, included in guidelines and used extensively. However, with budgetary restrictions, that intervention may be delivered very differently in practice. It may be less frequently, over fewer sessions, or by minimally trained assistants. Even minor changes can influence results,2 and apparently subtle differences can have profound effects.

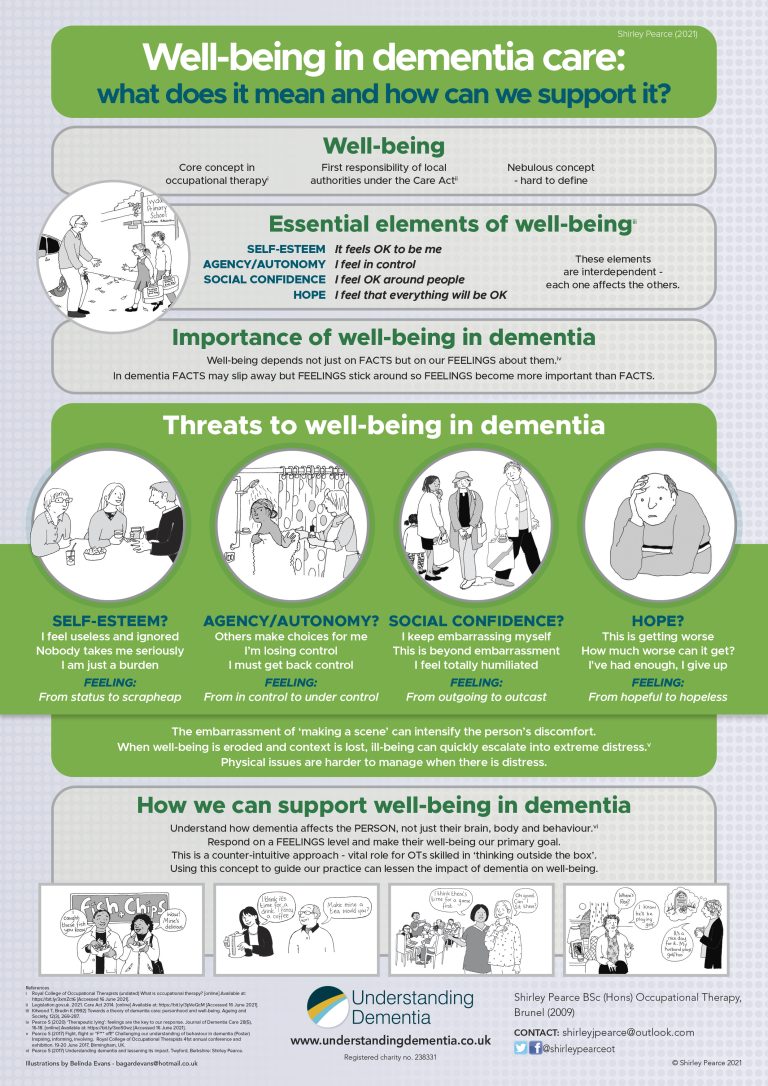

How often do we stop to consider what the person on the receiving end makes of our interventions? How does it feel to be in their shoes? Kitwood and Bredin3 described four feelings that are necessary for well-being. Dementia has its own way of sapping positive feelings, and if we’re not very careful, we can, inadvertently, make things worse.

Self-esteem

People with dementia often say that they feel useless and ignored, and some now use the slogan ‘Nothing about us, without us’. But what must it do to their self-esteem if our efforts to include them in consultations make them feel that we are talking about them, across them? We may have ticked an imaginary box marked ‘inclusion’, but does the person really feel included? If we need to discuss their situation with a health professional or a family member, it’s better to do that out of earshot, or in writing. Then we can focus our attention fully on the person during any consultation.

Agency/autonomy

Just like anyone else, people with dementia like to make their own choices. But well-meaning carers often take over and make choices on their behalf – which may well not be what the person would have chosen for themselves. When we set goals with someone living with dementia, how does that feel to them? Are the goals really theirs, or ours? The person may go along with what we suggest, but sometimes people tell us what they think we want to hear…

Social confidence

Dementia puts the person at constant risk of embarrassing themselves. Reminiscence can be a wonderful tool, mentally transporting them back to happier and more confident times. But even this activity can cause problems if we’re not careful how we do it. Old photographs can trigger lovely memories – but if we keep asking ‘Who are these people?’ or ‘When was this taken?’ the person may not be able to tell us. Perhaps they’re not in a photo because they were behind the camera. In those days selfies usually involved a tripod, a timer and a quick dash into position before the camera clicked. So an album may not contain any photographs of its owner.

And the question ‘Do you remember?’ can be too challenging altogether. If they say ‘Yes’, there may be further questions, so it’s often easier for them just to say ‘No’. Instead of asking questions, we can admire the scenery, the vehicles or the clothes in a photo, and then listen carefully to their response. That may lead us down a fascinating conversational trail and teach us something we didn’t know before.

Hope

Dementia is a progressive degenerative condition, and will inevitably get worse. Memory Clinics use questions to assess the person’s mental and cognitive abilities, in order to find out what we, and they, are dealing with. At follow-up appointments, questions can show how far the person has deteriorated since their last visit. But such questions are designed to highlight impairments, so it can feel to the person as if we are deliberately trying to catch them out. A friend’s mother emerged from her memory test in tears, saying: ‘He made me feel so stupid’. Intense questioning can even trigger traumatic memories for anyone who has been interrogated in the past.

We need to learn how to be a ‘buddy’ to the person with dementia, so they know we’re on their side. That will build up their confidence and enable them to function at their best.

How we are with the person with dementia can make as much difference to them as what we do.

These concepts are discussed further in our interactive online training courses for family carers and professionals working in health and social care.

For more details contact us via https://understandingdementia.co.uk/

Footnotes

1. Kitwood T (1997) Dementia reconsidered: the person comes first. Open University Press: Maidenhead.

2. Cove, J. (2013) Effectiveness of weekly Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) and the impact of additional carer training for people with dementia. Doctoral Thesis. University College London.

3. Kitwood T, Bredin K (1992) Towards a theory of dementia care: personhood and well-being. Ageing and Society 12 269-287