There’s no place like home

How many times do we hear someone with dementia say ‘I want to go home!’ It often happens in residential care facilities in the afternoon or evening, where it is known as ‘sundowning‘. I don’t find that label particularly helpful – I like to go home too at the end of a tiring or stressful day, but I don’t have dementia so no-one thinks anything of it.

This desire to go home was discussed in the programme ‘Am I home?’ BBC Radio 4 – ‘Am I Home?’ – Life in a Dementia Village which was broadcast recently on Radio 4. A member of staff at a care home described explaining to residents: ‘This is your home’ and Sue, a family carer, said she ‘had to’ tell her mother repeatedly that she was now living in a care home. But in my view, if she had to do it repeatedly, perhaps it wasn’t working…

I used to make this mistake too – my mother-in-law had dementia and she would ring several times a night, saying she couldn’t afford to stay in ‘this hotel’ and asking us to take her home. My husband would get more and more exasperated with each call, so he would pass the phone to me. It was easier for me to be patient with her – I had worked with people living with dementia before, and besides, she wasn’t my mother. I used to ‘reorientate’ her by talking through the contents of her room and explaining that she wouldn’t have all her clothes and books with her or her own pictures on the walls if she was in a hotel. She would thank me profusely and say she felt much better now, and then put the phone down. And I would congratulate myself for doing a really good job, until, a few minutes later, the phone would ring: ‘When are you going to take me home?’ And we would have the same conversation over and over again. I now realise that although the answer I gave her might have been strictly correct, it wasn’t the right answer for her.

In the radio programme Sue made the point that her mother Maureen didn’t remember the home she had come from when she moved into residential care – she meant the one she had lived in as a child with her parents. I’m not so sure this is always the case.

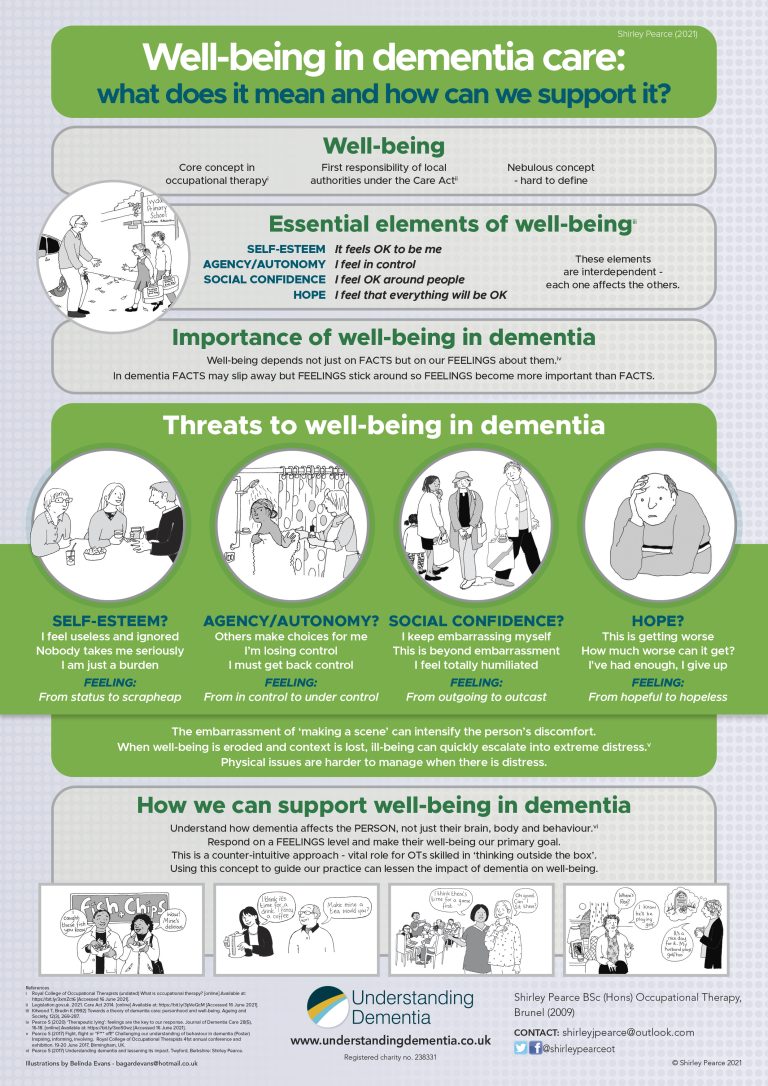

Basically, home is where we belong and where we can be ourselves – a safe retreat from anything that feels alien. Whenever we have a bad day at school or work, or we’re on a trip has gone wrong, or even at the end of an action-packed holiday, we long to go home. Home – to that place where everything makes sense. But in dementia, things are increasingly not making sense. Our memory system records and stores the feelings of what has just happened, but in dementia, more and more often the facts are not stored, so they just slip away. So for the person with dementia, feelings become more important than facts.

Without access to that constant stream of recently-stored facts that the rest of us take for granted – the facts that tell us where we are, how we got here and why we came – the person can feel more and more disorientated and the longing for home can become unbearable.

If we contradict the person, however gently, to explain that they are at home, that can leave them with the feeling that everyone else knows more about their recent life than they do. How unnerving must that be? So it is hardly surprising when they argue with us and become distressed.

So what can we do about it? By listening carefully to the person we can find out more about the anxieties and concerns that are driving the question, and what explanation would be likely to satisfy them for the longest time. For my mother-in-law, who loved staying in hotels, her worry was the cost and whether she could afford the bill. All we needed, had I only known, was probably to explain that it was all paid for. That was the truth anyway. It was all being paid for out of her money, but that was a fact – a detail – that she didn’t need to know just then. She just needed to feel that everything would be OK. But we can never be certain what explanation will work because everyone is different. So we need to be prepared for a bit of trial and error. It’s worth experimenting with different answers until you find the one that works best for that person, and then use it each time they ask.

Then things will make more sense and the person can start feeling more at home – and that’s what matters most.

Follow this link for more information and a video explaining our approach and training from Understanding Dementia