Dementia Friendliness – what is it exactly? Awkward questions…

What do people with dementia need – people wearing badges and tick-box actions? Or for the rest of us to understand how to lessen the impact of their condition?

When David Cameron introduced the Dementia Friends campaign in 2013, I was doing consultancy work for the Contented Dementia Trust, home of the SPECAL method. The Alzheimer’s Society had publicly denounced SPECAL, despite published evidence of its effectiveness. Studies have shown improved quality of life for people living with dementia1 and their family carers2.

Dementia Friends sessions explain dementia with an analogy. Memories are represented by books stored on two bookcases: a sturdy oak one for feelings and flimsy plywood for facts. Recent memories go on the top shelves, with older ones lower down. Dementia somehow shakes these bookcases. As a result books fall off the upper plywood shelves. However, those on the lowest shelves remain, and the oak bookcase stands firm.

Each participant at the session pledges an ‘action’ and receives a badge showing that they are a Dementia Friend. Apparently there are over 3.5 million Dementia Friends – I may well account for a few myself.

I received my first badge for attending a conference on dementia. With an audience of over 100, this must have been a good opportunity for a Dementia Friends Champion to improve their tally of ‘Dementia Friends’. A hospital doctor gave a presentation on making his ward Dementia Friendly at a cost of £200,000.

They decluttered, reorganised and redecorated the ward with non-reflective and non-slip flooring and improved signage. That clearly benefitted everyone. But I could not see how it made the ward more ‘friendly’ towards people living with dementia. I asked how much money they had spent on staff training.

‘Oh no,’ he replied, ‘it wasn’t about training, it was about making the place more dementia-fr—’ He stopped in his tracks. ‘Oh! I see what you mean!’ It hadn’t occurred to him that staff education might improve the experience of patients with dementia. Moreover, it was hard to find, because the improved signage did not extend as far as the corridor, and there was another ward with a similar ame.

I got a second badge when I attended a Dementia Friends session to find out more about the campaign.

The third one was for attending a Dementia Friends Champion training course. As a health professional specialising in dementia, I naturally wanted to learn everything I could about the condition. I asked the trainer questions to help me understand it better.

- Question: What evidence is there for this explanation? (As a health professional, I need to know that …)

Answer: ‘It’s not meant to be scientific.’ - Question: How do the ‘books’ get back on the ‘bookcase’ when the person recalls something that they couldn’t earlier?

Answer: ‘It’s only an analogy.’

There was no mention of what happens when new memories are laid down after the onset of dementia. In my view this is a key difference between normal memory and dementia.

Some of the ‘actions’ pledged sounded less than helpful, but the trainer accepted them all. Having started by admitting that she was not a dementia expert, perhaps she didn’t know which ones to reject.

That evening she rang me: ‘I think you are going to find it difficult to deliver the Dementia Friends sessions. As a mental health professional, you know too much.’

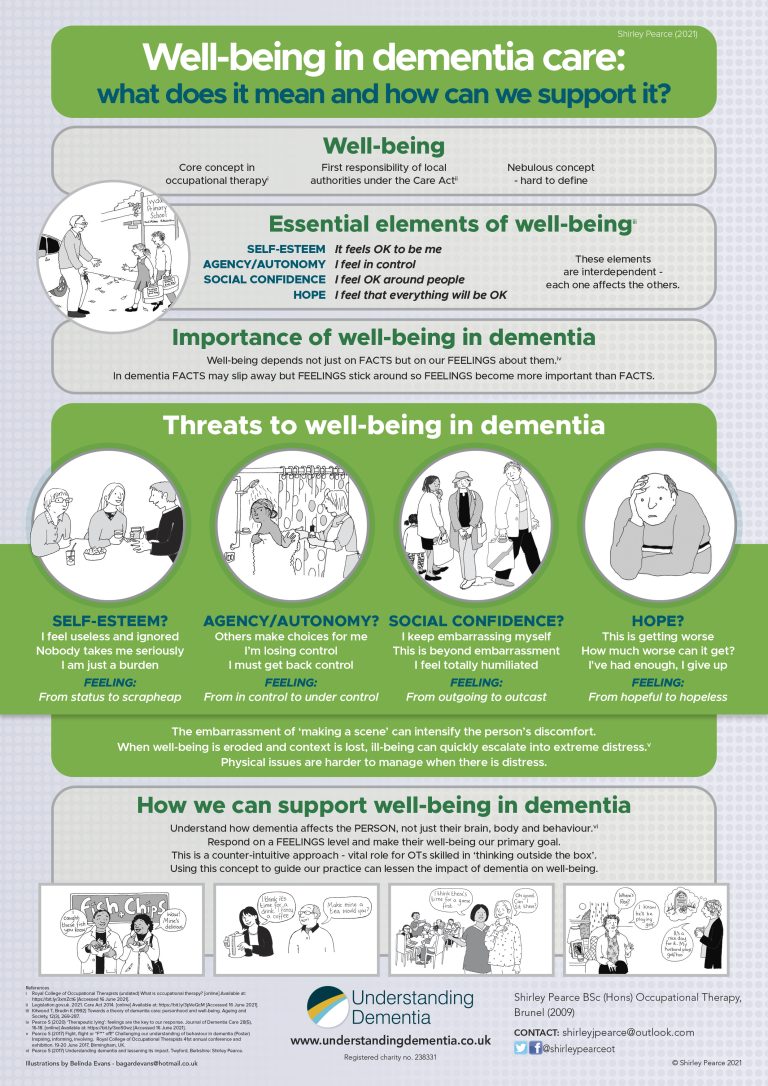

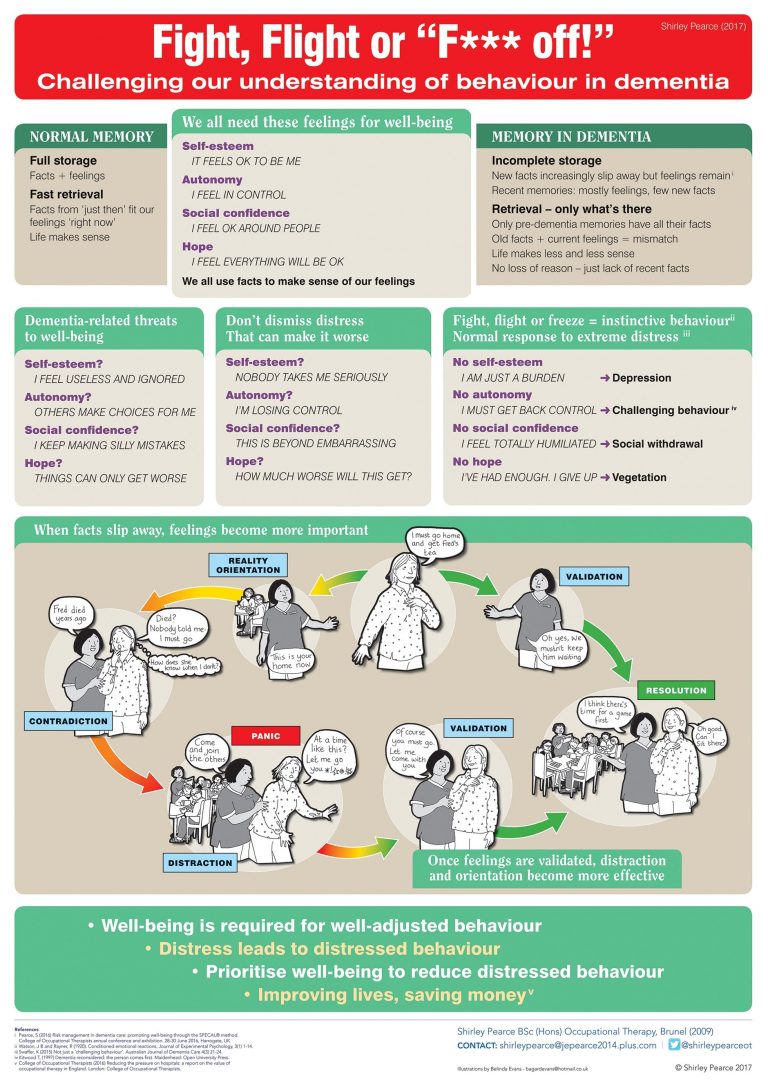

I know of no other field where in-depth subject knowledge represents a barrier to spreading awareness. However, I did not deliver any sessions because I had other ways to help people understand dementia. In 2018 I set up Understanding Dementia to bridge the gap between awareness and a real understanding of the condition. Our training focuses on how dementia affects the person, and how we can lessen its impact on them.

The Alzheimer’s Society says that Dementia Friends Information Sessions are not ‘training’. However many of its employees describe it as such, so there is a lot of misunderstanding. A care home manager told me that registering with Dementia Friends has made staff training unnecessary. Another health professional claimed that Dementia Friends training (sic) was accredited by the Alzheimer’s Society.

I can understand that error, since the government offered a financial incentive for businesses to sign up. NHS England set up the Quality Payments System for pharmacies in 2016. There were several criteria; one for 80% of the staff to be “trained [sic] ‘Dementia Friends’”. Another was that 80% had been on a Level 2 Safeguarding course. So this gave a Dementia Friends the equivalent ranking to a mandatory professional training course.

Conversely, there was no credit for staff having any actual dementia training. So attending a Dementia Friends session effectively outranked even a doctorate in Dementia Studies. Presumably no-one complained, because becoming a Dementia Friend was so easy and quick. They could even do it in their coffee breakby watching a five-minute video online. I have no wish to knock any attempt to raise awareness of dementia. However one of the unintended consequences has been healthcare companies viewing these sessions as a free alternative to specialist training.

I did mention that I had four Dementia Friends badges. When my car had a puncture, I found the fourth one embedded in the tyre.

Learn more about our training from Understanding Dementia for health and care professionals and family carers.

1 Pritchard EJ and Dewing J (2001) A multi-method evaluation of an independent dementia care service and its approach. Aging and Mental Health, 5(1) 63-72.

2 McCrae N and Penhallow J (2018) SPECAL: first evaluation of a course for carers. The Journal of Dementia Care 26(6) 30-33.