Fight, flight or “F*** off!” Challenging our understanding of behaviour in dementia

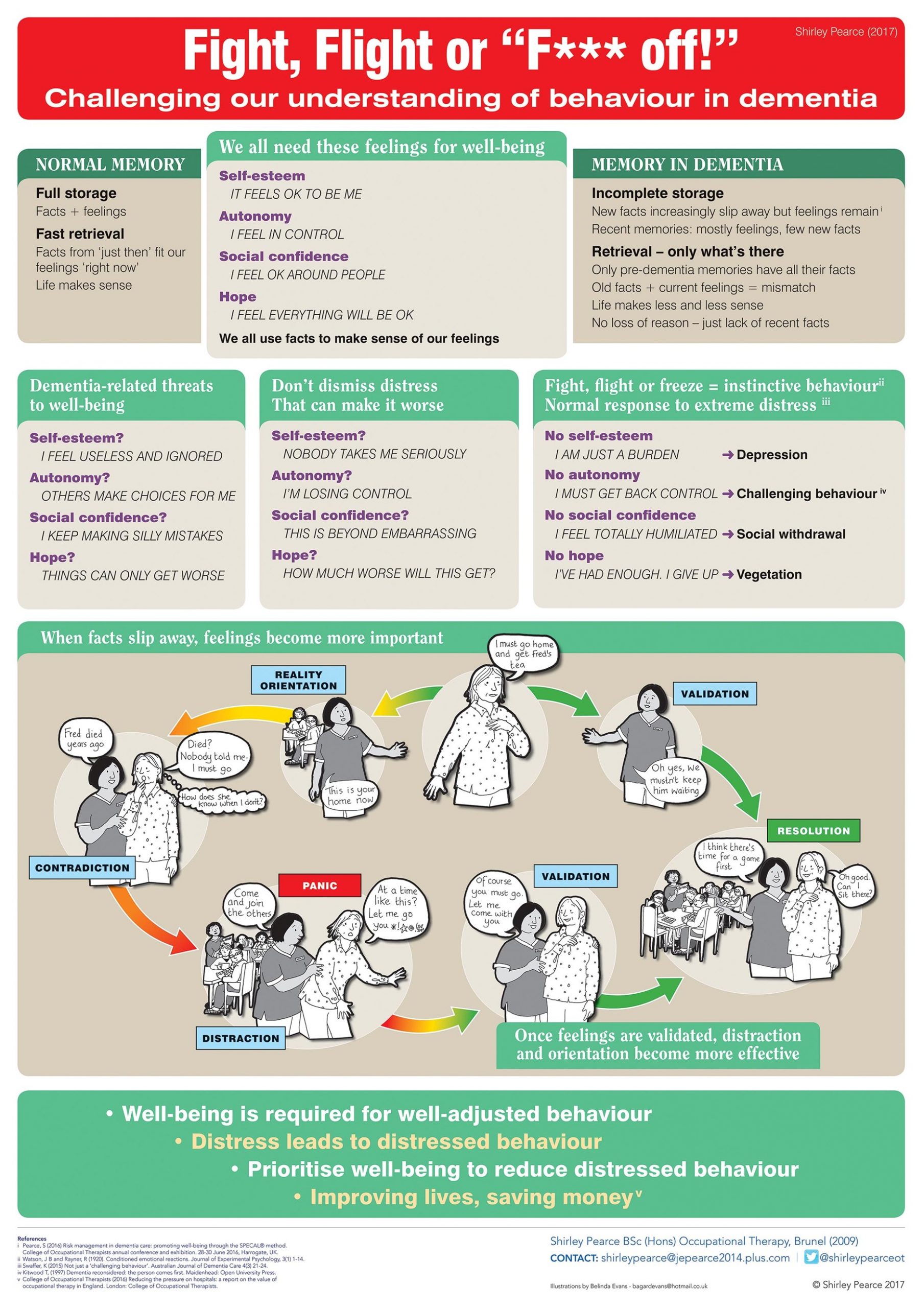

I displayed this poster at the Royal College of Occupational Therapists’ annual conference in 2017 and at the OT Show. The aim was to challenge the view that ‘challenging behaviour’ is just a characteristic of dementia, something that is ‘only to be expected’ at certain stages of dementia, and that all you can do is just deal with it as and when it happens.

Behavioural incidents upset everyone involved. Moreover, they often precipitate a transfer to more restrictive and expensive care settings. If we could only understand their causes, prevention would start to become a possibility.

Normal memory brings a constant supply of recent factual information that provides the context for our current feelings. Dementia increasingly disrupts this supply.1 Consequently, people who live with dementia may misinterpret events as threatening, even when they seem innocuouswhen to others. Furthermore, in his book Dementia Reconsidered, Tom Kitwood2 observed that even well-intentioned caregivers can inadvertently cause distress.

As long ago as 1920, Watson and Rayner3 were writing about extreme reactions to perceived threats. Too often we don’t recognise such responses for what they are; instead, we treat them merely as symptoms of the person’s condition, and we ignore the distress that triggered them. Then we are surprised to discover that our treatments often achieve little or no benefit, and potentially some harm.

In dementia, well-being does not depend on ‘well-managed’ behaviour. Conversely, restoring well-being can even help re-establish normal behaviour. Health professional, informal carer, dementia rights activist and PhD candidate with lived experience Kate Swaffer highlights the preventive aspect of good care.4 Not only is restoring well-being the desired outcome of an intervention, but it should also be the first step in that intervention.

In dementia, because feelings become more important to the individual than facts,5 this can be easier to achieve than in most other conditions, reducing restraint and medication costs and side-effects. If the health and social care professions understood this better, they could save people with dementia a great deal of distress, their carers a lot of heartache and our beleaguered NHS a significant amount of money.

Download our training leaflet for health and care professionals: https://understandingdementia.co.uk/training-health-care-professionals/

1 Pearce, S (2016) Managing risk in dementia care: promoting well-being through the SPECAL® method. College of Occupational Therapists annual conference and exhibition. 28-30 June 2016, Harrogate, UK.

2 Kitwood, T (1997) Dementia reconsidered: the person comes first. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

3 Watson, J B and Rayner, R (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3(1) 1–14.

4 Swaffer, K (2015) Not just a ‘challenging behaviour’. Australian Journal of Dementia Care 4(3) 21-24.

5 Garner, P (2008) The SPECAL Photograph Album. 3rd ed. Hawling: Windrush Hill Books.

Shirley Pearce – 12/01/2019