Dementia: learning from the expert in our care

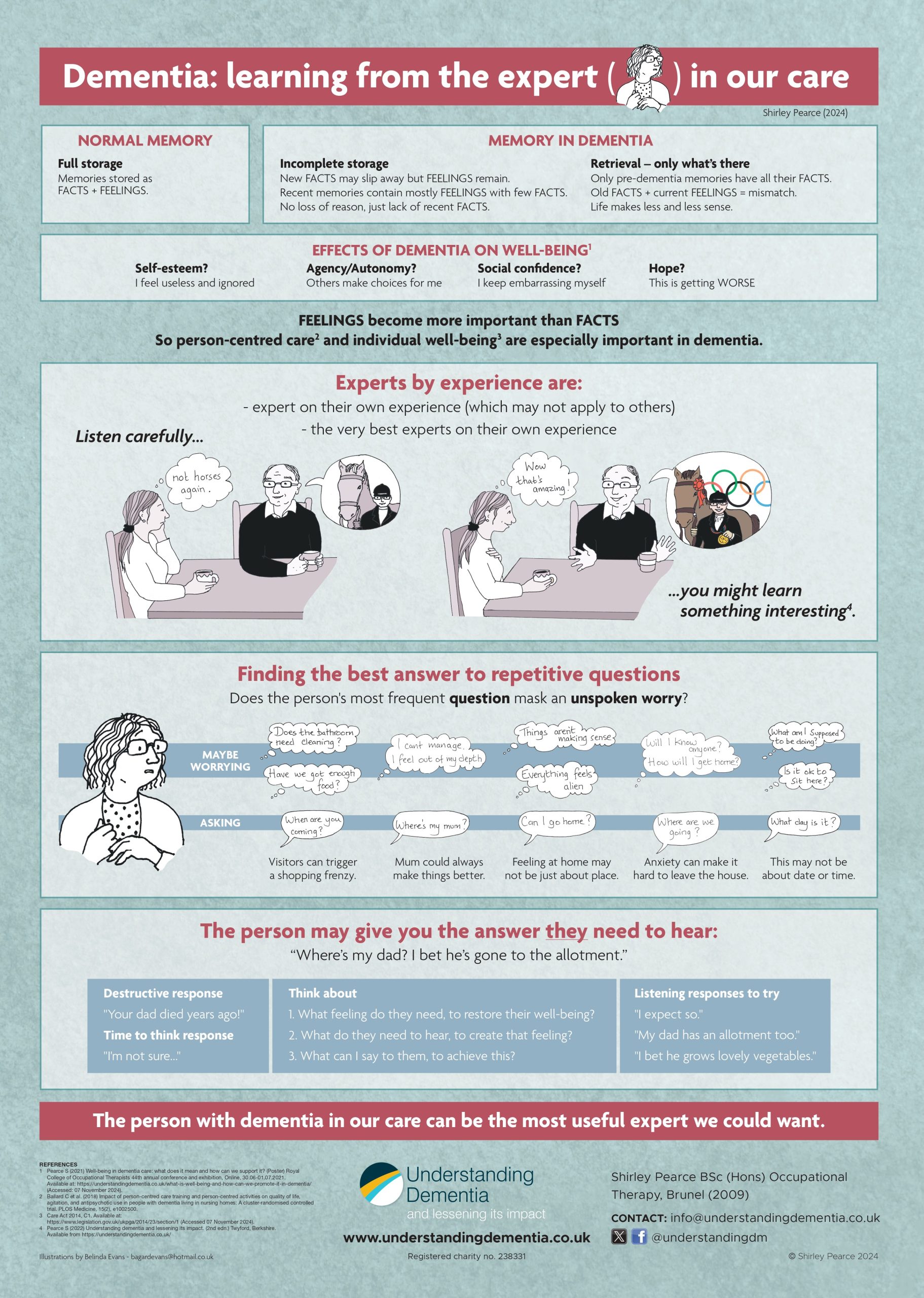

I displayed this poster at the UK Dementia Congress in Coventry this week. There was a lot of talk about experts by experience and the importance of co-production, focus groups etc. These are used in devising training and deciding policy.

Experts by experience understand their own situation best. However their experience may not apply to others, even with the same condition. The most active and articulate experts are likely to be in the early stages of Young Onset Dementia or similar conditions. They therefore cannot represent the situations of older people in the later stages, who are less able to speak up. So they tend to get ignored.

I once heard a family carer at a dementia conference describing their spouse as ‘suffering from dementia’. An advocate for ‘living well with dementia’ shouted them down. They insisted that the person was not ‘suffering from’, but just ‘living with’ dementia. However, that carer knew what his wife was going through far better than an activist who didn’t know either of them.

Professionals working with patients or clients with dementia often overlook the most relevant expert of all – the person right in front of them on their caseload. If that person is struggling to make sense of their surroundings and doesn’t feel understood or properly listened to, they may become angry, frustrated and upset. They are likely to behave in ways that are difficult for others to understand and cope with. All too often the focus of professional interventions is on managing behaviour rather than listening to the person and learning from them.

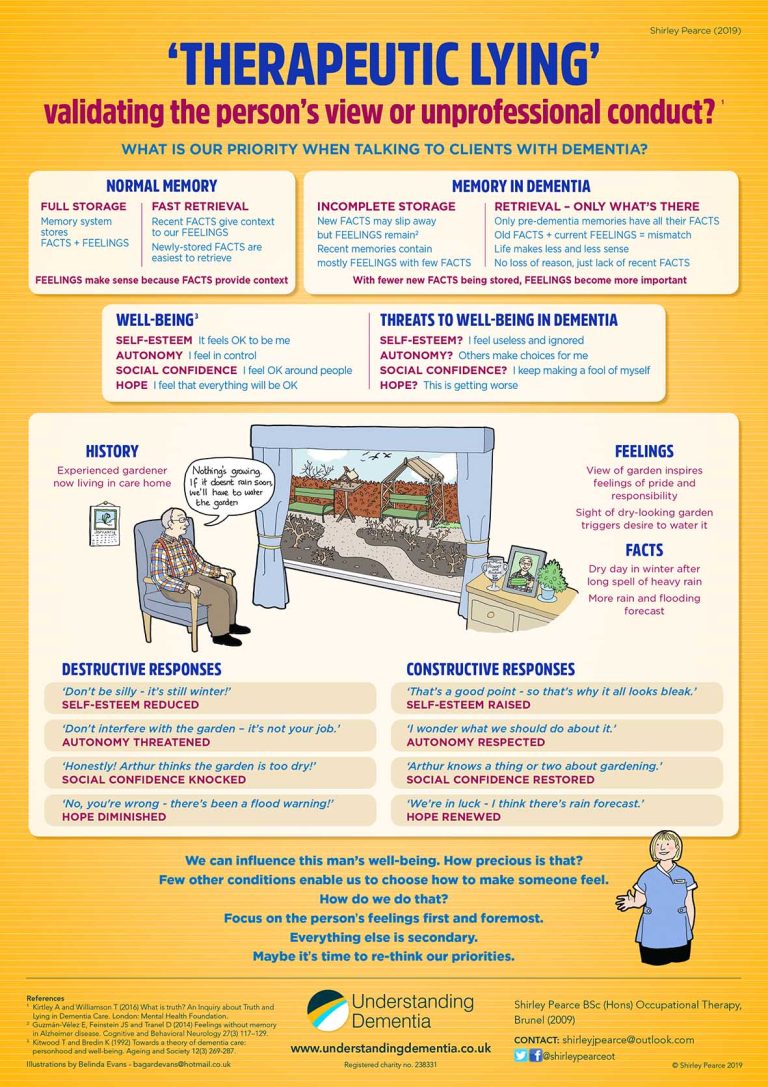

Repetitive questions can be very irritating, especially for family carers who may be hearing them 24/7. But responding each time with the same factual answer may not help, especially if the question masks an unspoken worry.

“Where’s my mum?” doesn’t necessarily mean “Is she still alive?” or “Where is she buried?” It could just mean: “I feel out of my depth.”

Similarly “Can I go home?” may not refer to a geographical address, but rather home in the sense of that place where we can be ourselves, and where everything makes sense. For the person with dementia, things are increasingly not making sense, and their suppoundings may feel more and more alien. So taking them to their last house, or back to their childood home, may only add to their confusion.

The best answer to start with may be a non-committal response to give us more time to see the person’s viewpoint. For example, ‘I don’t know…’ puts us on the same level as the person who’s asking. They may then elaborate with more information that gives us a clue to the reason for their question, or any unspoken worry behind it.

If we listen to what they say, how they say it (including facial expressions or other body language) and what they don’t say, that can tell us a lot. They can then become the most useful expert we could want.

Follow this link for more information and a video explaining our approach and training from Understanding Dementia